Policy crossroads and the end of the public health emergency due to COVID-19

This is part of a three-part series on significant implications of the end of the Public Health Emergency (PHE).

The end of the Public Health Emergency on May 11, 2023 is likely to mark a transitional point in the rapidly evolving arena of virtual care services and not a dramatic end of coverage. Coverage of virtual care services will continue to evolve significantly over the next five years given the exponential growth in the public’s awareness of, and comfort with, these services — all hastened by the COVID-19 Federal Public Health Emergency.

The U.S. Congress and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) used its authority during the PHE to significantly expand Medicare coverage for virtual care services, covering telehealth visits in urban areas and from patient’s homes. In addition, Medicare began covering a wide range of clinical services virtually such as behavioral health and physical therapy; it also expanded coverage for different service delivery modalities to include audio-only visits. As a result of the changes, Medicare became a leading payer for virtual care nationally between 2020 and 2022. Over this same period, private insurers and state Medicaid programs largely followed Medicare’s lead by expanding their own virtual care coverage.

One of the consequences of the PHE is that most payers have embraced Medicare’s basic definitional structure for types of virtual care services. As a part of this typology, virtual care services are divided into two general buckets of services: telehealth visits (physician office visits conducted via audio and video technology), which are typically prohibited by statute in urban areas or a patient’s home; and Communication Technology-Based Services (CTBS) which can be conducted anywhere. CTBSs include: remote patient monitoring (RPM); virtual check-ins (brief patient-to-clinician exchanges); e-visits (online portal or email visits); and e-consults (clinician to clinician interaction).

With the end of the PHE on May 11, Medicare coverage of virtual care services and coverage offered by other payers will change. The details and scope of this change have many stakeholders concerned and confused. HMA has a keen sense for which virtual care services may get a new lease on life in the coming months and which are likely to be hotly debated in the years ahead. The one certainty is that the last 3 years have altered the landscape for virtual care services for years to come.

Shift in Virtual Care Landscape

As a result of the statutory geographic limitations and restrictions placed on traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare coverage, use of telehealth services was minimal most of the last decade, with only one-quarter of 1 percent (0.25%) of beneficiaries in FFS Medicare using virtual care services.[1] Even among Medicare Advantage plans and Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), neither of which which face the same restrictions, virtual care was utilized very rarely before 2019.

This sluggish use of telehealth was radically altered when HHS used its PHE authority to relax constraints on the use of use virtual care services by Medicare beneficiaries and providers.[2],[3] Among the most consequential changes made by policymakers at the outset of the PHE were:

- Enabling telehealth services to be provided anywhere (e.g., urban areas and patients’ homes);

- Allowing Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) and Rural Health Clinics (RHC) to conduct virtual care services;

- Granting various types of clinicians permission to deliver virtual care services;

- Enabling new patients to receive virtual care services;

- Authorizing audio-only services;

- Permitting telehealth services for more than 200 different types of clinical services (e.g., mental health, emergency department, physical and occupational therapy, critical care, inpatient care);

- Relaxing HIPPA rules to enable the broad use of smartphones for virtual care.

Due to these policy changes, rates of virtual care skyrocketed during the PHE (Figure 1). In April of 2020 the number of Medicare claims for any type of virtual care service exceeded 9 million, while 2019 the number of these services provided monthly never exceeded 100,000 (Figure 1). On an annual basis, from 2019 to 2021 the number of virtual care visits jumped from roughly 1 million to 39 million and the number of unique beneficiaries receiving these services increased from 300,000 to nearly 12 million.

Figure 1: Number of Virtual Care Service Visits, Number of Unique Medicare Fee-For-Service Beneficiaries, and Number of visits per Utilizer by Month, December 2019 to December 2021.

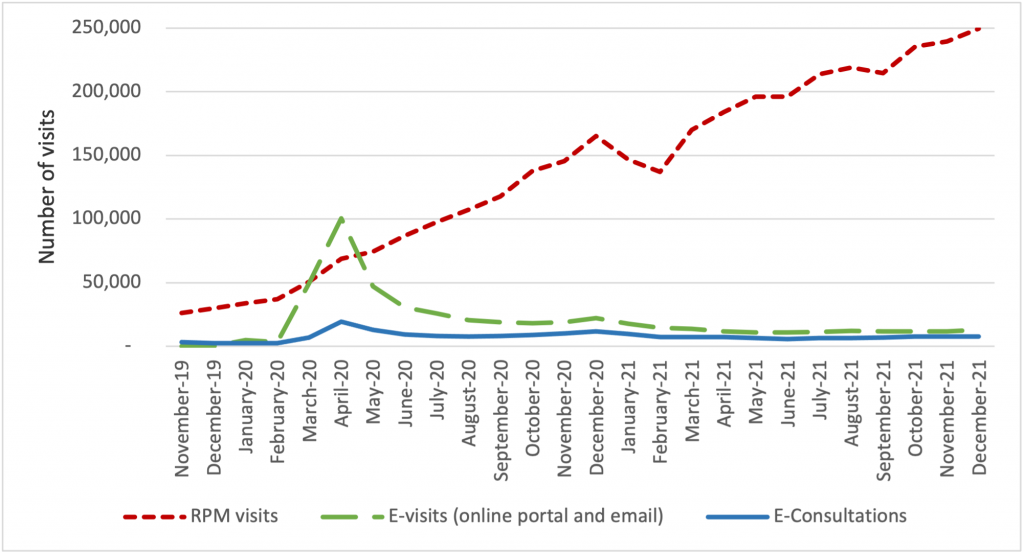

The growth of virtual care services has largely been driven by an increase in telehealth visits, but we observe important trends in the use of CTBSs, as well. In late 2021, more than 90 percent of visits were associated with telehealth, while 10 percent were associated with CTBSs. Early in the PHE, all of these service types experienced an initial, abrupt increase in use (Figure 2). By contrast, the growth in the use of remote patient monitoring (RPM) has been continuous since 2020. The growth in use of RPM reflects the general movement of services into patients’ homes and has been accelerated by specialist such as cardiologists and endocrinologists beginning to leverage the power of RPM. We expect greater diffusion and use of RPM and other CTBSs in the next five years.

Figure 2: Number of Virtual Care Service Visits for Remote Patient Monitoring, Virtual Check-ins, E-visits, and E-Consultations by Month, December 2019 to December 2021.

Policies temporarily in place until the end of 2024

During the PHE, Congress made critical long-term changes to Medicare’s coverage of virtual care services that continued to spur the use of these services and offer access to care for beneficiaries. In 2021, Congress changed the law to permanently allow Medicare beneficiaries to receive behavioral/mental telehealth services regardless of location (urban or rural) and for this care to be available to patients in their own homes.

In 2022, Congress severed the link between the PHE declaration and Medicare coverage policies for virtual care services, extending those benefits through the end of calendar year 2024. We expect that coverage for all telehealth services will receive considerable attention from federal policymakers and stakeholders towards the end of 2024.

Immediate impact of expiring policies

Certain aspects of Medicare’s virtual care policies will, however, terminate May 11, 2023, when the PHE declaration comes to an end. Several of the expiring policies have a broader impact beyond the Medicare program, affecting patients insured by private payers and State Medicaid programs.

Specifically, when the PHE ends, policymakers will need to address the following anticipated changes:

- The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) will return to imposing penalties on providers who violate the provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) by using public-facing remote communication technologies which are not HIPAA-compliant. This may prohibit the use of some of the most common smartphone-based video conferencing tools for health care visits.

- Medicare beneficiaries without an existing relationship with a clinician will be unable to receive CTBSs such as RPM, virtual check-ins, and e-visits.

- Providers will no longer be allowed to provide virtual care services across state lines, because most state medical licensure boards will return to pre-PHE policy.

- Federal rules from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) may revert to the pre-PHE requirement that clinicians establish a patient-provider relationship in-person before being permitted to prescribe controlled substances for substance use disorder treatment.

Potential policy changes occurring before 2025 As explained earlier, Medicare coverage for many virtual care services will remain in place for the next 19 months. Before the end of 2024, Congress will need to address several policy questions, and among the most widely debated are whether to:

- Restore Medicare’s statutory prohibition on telehealth services being delivered in urban areas or in home settings;

- Allow Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics to provide telehealth services to Medicare beneficiaries; or

- Continue to cover audio-only telehealth visits under Medicare.

Lawmakers will look to payers, patients, and providers for feedback before making these policy decisions. Among the most critical pieces of information they will also consider will be the results of the study Congress has required of HHS regarding trends in the use of virtual care. This study’s final report is due in 2026, which has led some to speculate that Congress will delay action on virtual care coverage policy until then. In the meanwhile, we expect HHS will be assessing the overall volume of virtual care use, who is using which types of services, and the levels of related fraud and abuse.

Looking Ahead

In the United States, our experience during the acute phase of the pandemic demonstrated that patients and providers are more receptive than previously thought to utilizing digital technologies for the delivery of care. This experience may also influence policymakers’ decisions about reimbursement and coverage of wearable devices, as well as other cutting-edge tools that rely on artificial intelligence or machine learning.

HMA believes payers and providers alike can take steps now to strategically prepare for the still evolving and growing landscape of digital health care.

Based on the various changes that have occurred in the virtual care environment over the last 3 years, we are intently watching several areas of potential change in the practice of medicine and the ways payers set coverage policy. Below are some of the trends we anticipate in the years ahead:

- Continued use of virtual care services at levels observed in 2021.

- An expansion of CMS’s programs to protect against fraud and abuse related to virtual care.

- Notable growth in the use of RPM, and related services for physical and occupational therapy services.

- The proliferation of innovative home-based screening and testing technologies. We anticipate payers will encourage the use of these at-home tests for things like kidney function, liver function, and colorectal cancer screening in order to limit care delivery in higher cost settings.

- Growth in “virtual-first” insurance plans, where patients are encouraged to use virtual care first – prior to being seen in person. As these plan options expand, we anticipate virtual care use will rise, and reimbursement rates will begin to change.

Virtual care services are primed for additional growth and HMA is working with a wide variety of payers, providers, and foundations to develop strategies for adapting to state and federal rules and regulations related to virtual care. Changes in this landscape will hinge on research CMS will complete by the end of 2026, and coverage decisions made by states and commercial payers. HMA is well positioned to assist stakeholders with work in this area and can leverage access to Medicare and Medicaid claims data to conduct health services research to illustrate geographic variations in the use of virtual care.

If you have questions on how HMA can support your agency before or after the end of the PHE, please contact our experts below.

Read other parts of this blog series:

[1] (2016) https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/Information-on-Medicare-Telehealth-Report.pdf

[2] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. March 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet

[3] HHS Administration for Strategic Preparedness & Response (ASPR). https://aspr.hhs.gov/legal/PHE/Pages/default.aspx